|

|

You've already seen the basics of classes and objects in Scala in the previous two chapters. In this chapter, we'll take you a bit deeper. You'll learn more about classes, fields, and methods, and get an overview of semicolon inference. You'll learn more about singleton objects, including how to use them to write and run a Scala application. If you are familiar with Java, you'll find the concepts in Scala are similar, but not exactly the same. So even if you're a Java guru, it will pay to read on.

A class is a blueprint for objects. Once you define a class, you can create objects from the class blueprint with the keyword new. For example, given the class definition:

class ChecksumAccumulator { // class definition goes here }

You can create ChecksumAccumulator objects with:

new ChecksumAccumulator

Inside a class definition, you place fields and methods, which are collectively called members. Fields, which you define with either val or var, are variables that refer to objects. Methods, which you define with def, contain executable code. The fields hold the state, or data, of an object, whereas the methods use that data to do the computational work of the object. When you instantiate a class, the runtime sets aside some memory to hold the image of that object's state—i.e., the content of its variables. For example, if you defined a ChecksumAccumulator class and gave it a var field named sum:

class ChecksumAccumulator { var sum = 0 }

and you instantiated it twice with:

val acc = new ChecksumAccumulator val csa = new ChecksumAccumulator

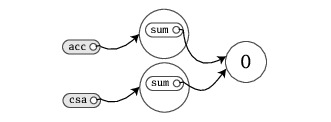

The image of the objects in memory might look like:

Since sum, a field declared inside class ChecksumAccumulator, is a var, not a val, you can later reassign to sum a different Int value, like this:

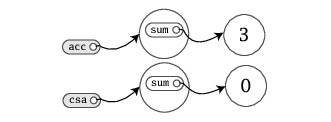

acc.sum = 3

Now the picture would look like:

One thing to notice about this picture is that there are two sum variables, one in the object referenced by acc and the other in the object referenced by csa. Fields are also known as instance variables, because every instance gets its own set of the variables. Collectively, an object's instance variables make up the memory image of the object. You can see this illustrated here not only in that you see two sum variables, but also that when you changed one, the other was unaffected.

Another thing to note in this example is that you were able to mutate the object acc referred to, even though acc is a val. What you can't do with acc (or csa), given that they are vals, not vars, is reassign a different object to them. For example, the following attempt would fail:

// Won't compile, because acc is a val acc = new ChecksumAccumulatorWhat you can count on, therefore, is that acc will always refer to the same ChecksumAccumulator object with which you initialize it, but the fields contained inside that object might change over time.

One important way to pursue robustness of an object is to ensure that the object's state—the values of its instance variables—remains valid during its entire lifetime. The first step is to prevent outsiders from accessing the fields directly by making the fields private. Because private fields can only be accessed by methods defined in the same class, all the code that can update the state will be localized to the class. To declare a field private, you place a private access modifier in front of the field, like this:

class ChecksumAccumulator { private var sum = 0 }

Given this definition of ChecksumAccumulator, any attempt to access sum from the outside of the class would fail:

val acc = new ChecksumAccumulator acc.sum = 5 // Won't compile, because sum is private

The way you make members public in Scala is by not explicitly specifying any access modifier. Put another way, where you'd say "public" in Java, you simply say nothing in Scala. Public is Scala's default access level.

Now that sum is private, the only code that can access sum is code defined inside the body of the class itself. Thus, ChecksumAccumulator won't be of much use to anyone unless we define some methods in it:

class ChecksumAccumulator {

private var sum = 0

def add(b: Byte): Unit = { sum += b }

def checksum(): Int = { return ~(sum & 0xFF) + 1 } }

The ChecksumAccumulator now has two methods, add and checksum, both of which exhibit the basic form of a function definition, shown in Figure 2.1 here.

Any parameters to a method can be used inside the method. One important characteristic of method parameters in Scala is that they are vals, not vars.[1] If you attempt to reassign a parameter inside a method in Scala, therefore, it won't compile:

def add(b: Byte): Unit = { b = 1 // This won't compile, because b is a val sum += b }

Although add and checksum in this version of ChecksumAccumulator correctly implement the desired functionality, you can express them using a more concise style. First, the return at the end of the checksum method is superfluous and can be dropped. In the absence of any explicit return statement, a Scala method returns the last value computed by the method.

The recommended style for methods is in fact to avoid having explicit, and especially multiple, return statements. Instead, think of each method as an expression that yields one value, which is returned. This philosophy will encourage you to make methods quite small, to factor larger methods into multiple smaller ones. On the other hand, design choices depend on the design context, and Scala makes it easy to write methods that have multiple, explicit returns if that's what you desire.

Because all checksum does is calculate a value, it does not need an explicit return. Another shorthand for methods is that you can leave off the curly braces if a method computes only a single result expression. If the result expression is short, it can even be placed on the same line as the def itself. With these changes, class ChecksumAccumulator looks like this:

class ChecksumAccumulator { private var sum = 0 def add(b: Byte): Unit = sum += b def checksum(): Int = ~(sum & 0xFF) + 1 }

Methods with a result type of Unit, such as ChecksumAccumulator's add method, are executed for their side effects. A side effect is generally defined as mutating state somewhere external to the method or performing an I/O action. In add's case, for example, the side effect is that sum is reassigned. Another way to express such methods is to leave off the result type and the equals sign, and enclose the body of the method in curly braces. In this form, the method looks like a procedure, a method that is executed only for its side effects. The add method in Listing 4.1 illustrates this style:

// In file ChecksumAccumulator.scala class ChecksumAccumulator { private var sum = 0 def add(b: Byte) { sum += b } def checksum(): Int = ~(sum & 0xFF) + 1 }

One puzzler to watch out for is that whenever you leave off the equals sign before the body of a function, its result type will definitely be Unit. This is true no matter what the body contains, because the Scala compiler can convert any type to Unit. For example, if the last result of a method is a String, but the method's result type is declared to be Unit, the String will be converted to Unit and its value lost. Here's an example:

scala> def f(): Unit = "this String gets lost" f: ()UnitIn this example, the String is converted to Unit because Unit is the declared result type of function f. The Scala compiler treats a function defined in the procedure style, i.e., with curly braces but no equals sign, essentially the same as a function that explicitly declares its result type to be Unit:

scala> def g() { "this String gets lost too" } g: ()UnitThe puzzler occurs, therefore, if you intend to return a non-Unit value, but forget the equals sign. To get what you want, you'll need to insert the missing equals sign:

scala> def h() = { "this String gets returned!" } h: ()java.lang.String

scala> h res0: java.lang.String = this String gets returned!

In a Scala program, a semicolon at the end of a statement is usually optional. You can type one if you want but you don't have to if the statement appears by itself on a single line. On the other hand, a semicolon is required if you write multiple statements on a single line:

val s = "hello"; println(s)If you want to enter a statement that spans multiple lines, most of the time you can simply enter it and Scala will separate the statements in the correct place. For example, the following is treated as one four-line statement:

if (x < 2) println("too small") else println("ok")Occasionally, however, Scala will split a statement into two parts against your wishes:

x + yThis parses as two statements x and +y. If you intend it to parse as one statement x + y, you can always wrap it in parentheses:

(x + y)Alternatively, you can put the + at the end of a line. For just this reason, whenever you are chaining an infix operation such as +, it is a common Scala style to put the operators at the end of the line instead of the beginning:

x + y + z

The precise rules for statement separation are surprisingly simple for how well they work. In short, a line ending is treated as a semicolon unless one of the following conditions is true:

// In file ChecksumAccumulator.scala import scala.collection.mutable.Map

object ChecksumAccumulator {

private val cache = Map[String, Int]()

def calculate(s: String): Int = if (cache.contains(s)) cache(s) else { val acc = new ChecksumAccumulator for (c <- s) acc.add(c.toByte) val cs = acc.checksum() cache += (s -> cs) cs } }

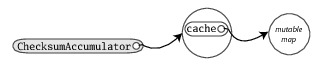

As mentioned in Chapter 1, one way in which Scala is more object-oriented than Java is that classes in Scala cannot have static members. Instead, Scala has singleton objects. A singleton object definition looks like a class definition, except instead of the keyword class you use the keyword object. Listing 4.2 shows an example.

The singleton object in this figure is named ChecksumAccumulator, the same name as the class in the previous example. When a singleton object shares the same name with a class, it is called that class's companion object. You must define both the class and its companion object in the same source file. The class is called the companion class of the singleton object. A class and its companion object can access each other's private members.

The ChecksumAccumulator singleton object has one method, named calculate, which takes a String and calculates a checksum for the characters in the String. It also has one private field, cache, a mutable map in which previously calculated checksums are cached.[2] The first line of the method, "if (cache.contains(s))", checks the cache to see if the passed string is already contained as a key in the map. If so, it just returns the mapped value, cache(s). Otherwise, it executes the else clause, which calculates the checksum. The first line of the else clause defines a val named acc and initializes it with a new ChecksumAccumulator instance.[3] The next line is a for expression, which cycles through each character in the passed string, converts the character to a Byte by invoking toByte on it, and passes that to the add method of the ChecksumAccumulator instances to which acc refers. After the for expression completes, the next line of the method invokes checksum on acc, which gets the checksum for the passed String, and stores it into a val named cs. In the next line, cache += (s -> cs), the passed string key is mapped to the integer checksum value, and this key-value pair is added to the cache map. The last expression of the method, cs, ensures the checksum is the result of the method.

If you are a Java programmer, one way to think of singleton objects is as the home for any static methods you might have written in Java. You can invoke methods on singleton objects using a similar syntax: the name of the singleton object, a dot, and the name of the method. For example, you can invoke the calculate method of singleton object ChecksumAccumulator like this:

ChecksumAccumulator.calculate("Every value is an object.")

A singleton object is more than a holder of static methods, however. It is

a first-class object.

You can think of a singleton object's name, therefore, as a "name tag" attached to the object:

Defining a singleton object doesn't define a type (at the Scala level of abstraction). Given just a definition of object ChecksumAccumulator, you can't make a variable of type ChecksumAccumulator. Rather, the type named ChecksumAccumulator is defined by the singleton object's companion class. However, singleton objects extend a superclass and can mix in traits. Given each singleton object is an instance of its superclasses and mixed-in traits, you can invoke its methods via these types, refer to it from variables of these types, and pass it to methods expecting these types. We'll show some examples of singleton objects inheriting from classes and traits in Chapter 12.

One difference between classes and singleton objects is that singleton objects cannot take parameters, whereas classes can. Because you can't instantiate a singleton object with the new keyword, you have no way to pass parameters to it. Each singleton object is implemented as an instance of a synthetic class referenced from a static variable, so they have the same initialization semantics as Java statics.[4] In particular, a singleton object is initialized the first time some code accesses it.

A singleton object that does not share the same name with a companion class is called a standalone object. You can use standalone objects for many purposes, including collecting related utility methods together, or defining an entry point to a Scala application. This use case is shown in the next section.

To run a Scala program, you must supply the name of a standalone singleton object with a main method that takes one parameter, an Array[String], and has a result type of Unit. Any standalone object with a main method of the proper signature can be used as the entry point into an application. An example is shown in Listing 4.3:

// In file Summer.scala import ChecksumAccumulator.calculate

object Summer { def main(args: Array[String]) { for (arg <- args) println(arg +": "+ calculate(arg)) } }

The name of the singleton object in Listing 4.3 is Summer. Its main method has the proper signature, so you can use it as an application. The first statement in the file is an import of the calculate method defined in the ChecksumAccumulator object in the previous example. This import statement allows you to use the method's simple name in the rest of the file.[5] The body of the main method simply prints out each argument and the checksum for the argument, separated by a colon.

Scala implicitly imports members of packages java.lang and scala, as well as the members of a singleton object named Predef, into every Scala source file. Predef, which resides in package scala, contains many useful methods. For example, when you say println in a Scala source file, you're actually invoking println on Predef. (Predef.println turns around and invokes Console.println, which does the real work.) When you say assert, you're invoking Predef.assert.

To run the Summer application, place the code from Listing 4.3 into a file named Summer.scala. Because Summer uses ChecksumAccumulator, place the code for ChecksumAccumulator, both the class shown in Listing 4.1 and its companion object shown in Listing 4.2, into a file named ChecksumAccumulator.scala.

One difference between Scala and Java is that whereas Java requires you to put a public class in a file named after the class—for example, you'd put class SpeedRacer in file SpeedRacer.java—in Scala, you can name .scala files anything you want, no matter what Scala classes or code you put in them. In general in the case of non-scripts, however, it is recommended style to name files after the classes they contain as is done in Java, so that programmers can more easily locate classes by looking at file names. This is the approach we've taken with the two files in this example, Summer.scala and ChecksumAccumulator.scala.

Neither ChecksumAccumulator.scala nor Summer.scala are scripts, because they end in a definition. A script, by contrast, must end in a result expression. Thus if you try to run Summer.scala as a script, the Scala interpreter will complain that Summer.scala does not end in a result expression (assuming of course you didn't add any expression of your own after the Summer object definition). Instead, you'll need to actually compile these files with the Scala compiler, then run the resulting class files. One way to do this is to use scalac, which is the basic Scala compiler, like this:

$ scalac ChecksumAccumulator.scala Summer.scalaThis compiles your source files, but there may be a perceptible delay before the compilation finishes. The reason is that every time the compiler starts up, it spends time scanning the contents of jar files and doing other initial work before it even looks at the fresh source files you submit to it. For this reason, the Scala distribution also includes a Scala compiler daemon called fsc (for fast Scala compiler). You use it like this:

$ fsc ChecksumAccumulator.scala Summer.scalaThe first time you run fsc, it will create a local server daemon attached to a port on your computer. It will then send the list of files to compile to the daemon via the port, and the daemon will compile the files. The next time you run fsc, the daemon will already be running, so fsc will simply send the file list to the daemon, which will immediately compile the files. Using fsc, you only need to wait for the Java runtime to startup the first time. If you ever want to stop the fsc daemon, you can do so with fsc -shutdown.

Running either of these scalac or fsc commands will produce Java class files that you can then run via the scala command, the same command you used to invoke the interpreter in previous examples. However, instead of giving it a filename with a .scala extension containing Scala code to interpret as you did in every previous example,[6] in this case you'll give it the name of a standalone object containing a main method of the proper signature. You can run the Summer application, therefore, by typing:

$ scala Summer of love

You will see checksums printed for the two command line arguments:

of: -213 love: -182

Scala provides a trait, scala.Application, that can save you some finger typing. Although we haven't yet covered everything you'll need to understand exactly how this trait works, we figured you'd want to know about it now anyway. Listing 4.4 shows an example:

import ChecksumAccumulator.calculate

object FallWinterSpringSummer extends Application {

for (season <- List("fall", "winter", "spring")) println(season +": "+ calculate(season)) }

To use the trait, you first write "extends Application" after the name of your singleton object. Then instead of writing a main method, you place the code you would have put in the main method directly between the curly braces of the singleton object. That's it. You can compile and run this application just like any other.

The way this works is that trait Application declares a main method of the appropriate signature, which your singleton object inherits, making it usable as a Scala application. The code between the curly braces is collected into a primary constructor of the singleton object, and is executed when the class is initialized. Don't worry if you don't understand what all this means. It will be explained in later chapters, and in the meantime you can use the trait without fully understanding the details.

Inheriting from Application is shorter than writing an explicit main method, but it also has some shortcomings. First, you can't use this trait if you need to access command-line arguments, because the args array isn't available. For example, because the Summer application uses command-line arguments, it must be written with an explicit main method, as shown in Listing 4.3. Second, because of some restrictions in the JVM threading model, you need an explicit main method if your program is multi-threaded. Finally, some implementations of the JVM do not optimize the initialization code of an object which is executed by the Application trait. So you should inherit from Application only when your program is relatively simple and single-threaded.

This chapter has given you the basics of classes and objects in Scala, and shown you how to compile and run applications. In the next chapter, you'll learn about Scala's basic types and how to use them.

[1] The reason parameters are vals is that vals are easier to reason about. You needn't look further to determine if a val is reassigned, as you must do with a var.

[2] We used a cache here to show a singleton object with a field. A cache such as this is a performance optimization that trades off memory for computation time. In general, you would likely use such a cache only if you encountered a performance problem that the cache solves, and might use a weak map, such as WeakHashMap in scala.collection.jcl, so that entries in the cache could be garbage collected if memory becomes scarce.

[3] Because the keyword new is only used to instantiate classes, the new object created here is an instance of the ChecksumAccumulator class, not the singleton object of the same name.

[4] The name of the synthetic class is the object name plus a dollar sign. Thus the synthetic class for the singleton object named ChecksumAccumulator is ChecksumAccumulator$.

[5] If you're a Java programmer, you can think of this import as similar to the static import feature introduced in Java 5. One difference in Scala, however, is that you can import members from any object, not just singleton objects.

[6] The actual mechanism that the scala program uses to "interpret" a Scala source file is that it compiles the Scala source code to Java bytecodes, loads them immediately via a class loader, and executes them.